Sarah Boomgaard

How much are we willing to pay for the transformation of our rugby squads?

What if you could not afford to support your team? What if you have been a diehard supporter of this team for decades but suddenly you did not have the financial means to see them play anymore? Rugby has become increasingly inaccessible to South Africans. Rugby and cricket are amongst the least accessible sports to members of the public; not only are they expensive to play but even the ability to enjoy a game from the comfort of your couch has become increasingly difficult.

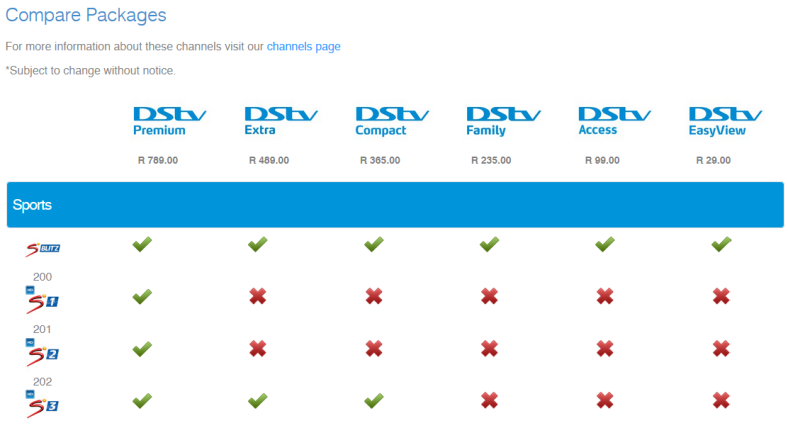

Rugby is not available to watch on any free to view channels in South Africa. To watch the Springboks or even your favourite club rugby team, one needs to have DSTV. Moreover, as rugby is generally only available on channel 201, one requires DSTV Premium – the most expensive package DSTV has to offer. SuperSport’s fairly recent decision to include Xhosa rugby commentary is admirable and definitely a step in the right direction. However as the majority of Xhosa speakers cannot afford the package the channel which rugby is available, SuperSport’s efforts to provide more linguistically and culturally inclusive commentary prove fruitless.

DSTV packages on offer with the sports channels available to each package.

Rugby is not available on any other DSTV channel, with the exception of SuperSport Blitz which showcases 5 minute highlights of various matches across a variety of sports. Five minutes is nothing. Five minutes is not enough to capture someone’s interest and we desperately need to capture people’s interest. Capturing the interests of the community would allow the rugby watching audience to grow, which would result in a more inclusive support base which in turn would help to establish a more diverse talent pool.

It may perhaps seem far-fetched to link transformation to the price of DSTV subscriptions, but the relationship is not all that difficult to understand. If people in impoverished communities, which in South Africa are predominantly people of colour, are unable to watch to rugby they will never grow to become rugby fans. If rugby fans are limited to the predominantly white affluent segments of the population, these segments will continue to make up the dominant rugby playing public. Politicians cannot continue to bemoan the slow pace of transformation without providing the general public access or the ability to watch rugby. Rugby needs to make its way to inexpensive − if not free − channels. The Springboks tests in particular should be made available to watch on SABC. It only makes sense that the public should be available to watch our national rugby team on our national broadcaster. This would allow for a strengthening of the rugby culture in our poorer communities.

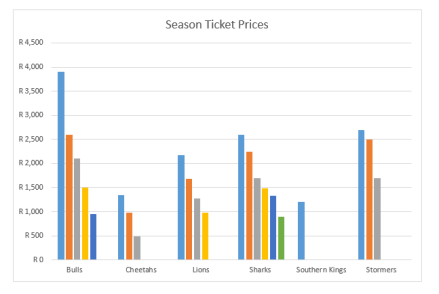

Graph 1: Season ticket prices correct at 19/06/2017

The prices of rugby tickets have also become problematic. Season ticket prices are borderline ludicrous. On average the Blue Bulls charge more per season ticket, more than any other union, where one can pay as much as R3900 for a Blue Bulls season ticket as can be seen in Graph 1 (right). The least expensive season tickets can be found in the Free State, the home of the Cheetahs. Generally ticket prices have also risen over the last few years, with inflation being the only apparent source of this increase. Most stadiums have not made any noticeable renovations which might explain the continued hikes in ticket prices. Despite DHL Newlands’ desperate need of renovation, it appears that Western Province Rugby has only upgraded their ancient sound system and splashed some red and yellow paint across the stadium to accommodate their sponsors, DHL. Yet a Stormers/ Western Province Rugby season ticket can cost you between R1700 and R2700.

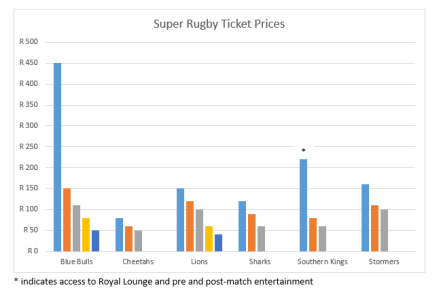

Graph 2: Super Rugby ticket prices correct at 19/06/207

Single match day tickets for Super Rugby games share more or less the same relationship between prices and respective unions as season tickets do. Once again, the Blue Bulls ask the most for their tickets whereas the Cheetahs ask the least (illustrated in Graph 2, right). The average price for a Super Rugby ticket is R114. While this may not seem like a lot of money to some people, for others it is choice between rugby tickets and food. I am by no means advocating for fee free tickets. Rugby unions need to earn an income and tickets are an easy way to do this. However, it would be prudent for rugby unions to make cheaper tickets available, even if these seats are limited to the lower sections of the stands behind the posts.

Access to the Springboks is almost impossible for poorer members of the community. A Rugby Championship ticket or a ticket to an international test can cost up to R650 at stadiums across South Africa. However, one need only pay R100 to see Bafana Bafana. The vast gap in proficiency, style or skill between the Springboks and Bafana are often cited as the primary reasons for the price discrepancy. Nevertheless the implications of the price of rugby tickets extends so much further than the “quality for money” argument. We are trying to build an inclusive national squad; one which is truly representative of the demographics of South Africa.

Forfeiting SuperSport’s broadcasting rights. Diminishing rugby union’s incomes. These are great asks. They require immense sacrifice. Yet the sacrifice we continue to make today is that much greater. If we continue to allow DSTV to hold exclusive broadcasting rights, if we continue to alienate the underprivileged through expensive tickets; the cost is immeasurable. We risk so much more than money. We risk the future of rugby in South Africa. We continue to sabotage all attempts to make transformation a reality. We could hold countless rugby clinics in traditionally black communities. We could invite numerous underprivileged schools to attend Super Rugby matches. It will not bring about change at the required pace. These are once off events in children’s lives. Without the development of a thriving rugby culture in impoverished communities, transformation will ever remain a pipe dream.